🔊 Listen to the story

Click Read to hear the story aloud. You can pause or stop at any time.

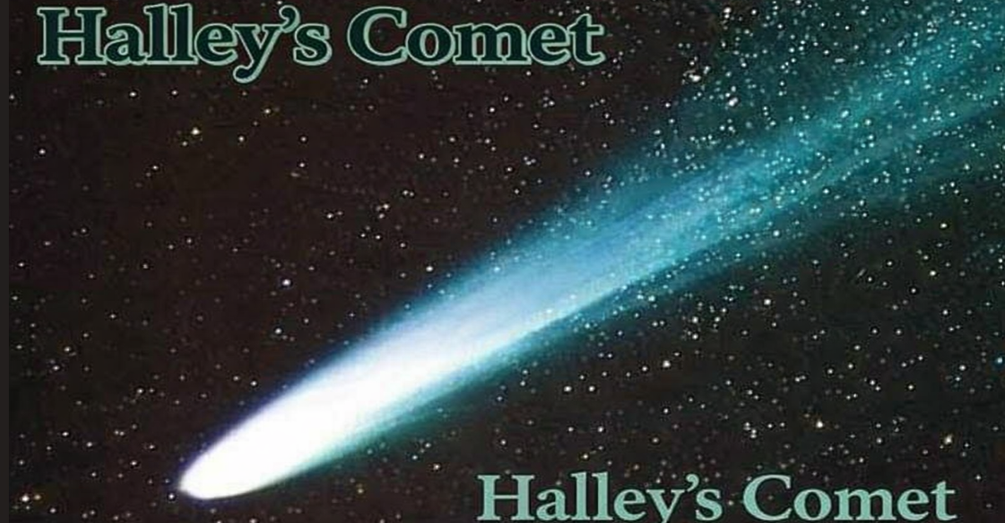

Halley’s Comet, Newton’s Falling Moon & the Secret Behind Taylor Series

When the kids were talking about space, I told them something I had never shared in any math class before. I said, quietly: “Thirty-eight years from now, Halley’s Comet will return. I won’t be here anymore. But you will be. And when you look up and see that pale streak across the sky, I want you to remember this moment — our Math Circle — and think of me.” The room went still. Cyrus was emotional, Rooz and Marc stopped talking and moving. We had a n emotional moment together.

Long before rockets, long before NASA, long before we could track anything with computers, there lived a curious man named Edmond Halley. He wasn’t rich. He wasn’t a superstar scientist like Newton. But he had one extraordinary gift: he could look at scattered, messy data and find patterns that no one else could see. In the early 1700s he noticed something peculiar — a bright comet seen in 1682 looked very much like ones recorded in 1607 and 1531.

Years later three brilliant friends—Sir Christopher Wren, Robert Hooke, and Edmond Halley—were arguing about what kind of curve a planet follows around the Sun. Wren, always mischievous, offered a bet:

“Astronomers told him he was wasting his time: “You can’t compare events 75 years apart”; “The orbits are different”; “The math is impossible.” Halley ignored them. After months of calculation, he made one of the boldest statements in scientific history: “They are the same comet. It returns every 76 years. It will be back in 1758.” This was the first time any human predicted a cosmic event so far into the future — and he was right.”

Hooke bragged that he knew the answer but did not want to spoil the bet. Halley, curious and determined, rode all the way to Cambridge to ask Newton. When he said, “What shape would the orbit be if gravity pulls as the inverse square of distance?” Newton quietly replied,

But Halley did not do it alone. He had a secret weapon: Isaac Newton. Newton had just discovered something shocking — something that changed how humans understood the universe. He realized that the same force that pulls an apple down also pulls the Moon toward the Earth. The Moon is falling, but because it keeps missing the Earth as it falls, it stays in orbit. When Halley asked Newton to explain how comets move, Newton used an idea that was revolutionary for its time: you can understand a complicated path by breaking it into tiny steps.”

Start with gravity here; Measure a small change there; Approximate the motion step by step; Tiny steps → Giant arcs; Small formulas → Predictions across the sky.

This simple, brilliant idea — using small changes to understand big curves — eventually grew into what we now call Taylor Series. It is the mathematics of “little steps,” the same idea that let Halley predict a comet and Newton map the orbit of the Moon.

And now in this adventure you will use that same idea. Not to find comets. Not to save astronauts. But to understand something just as magical: How small pieces of information can reveal the shape of an entire function.

And maybe — just maybe — when Halley’s Comet returns in 38 years, you will look up at the night sky and whisper, “We learned this with Dr. Super.”