🔊 Listen to the story

Click Read to hear the story aloud. You can pause or stop at any time.

The Thousand-Year Journey to the Power Rule

Over a thousand years ago, in the golden-age city of Baghdad, a quiet Persian scholar named Khwārizmī (the work Algorithm comes from his name) wandered through the long halls of the House of Wisdom, surrounded by scrolls from Persia, India, Greece, and China. He believed something extraordinary: Math should be a language — not a list of tricks.

So he wrote a book called al-Jabr wa’l-Muqābala, (Restoring and Balancing), the first true algebra text. Because of him, we have: the word algebra; the digits 0–9 used worldwide; andthe word algorithm (from al-Khwārizmī).

His book let mathematicians finally write ideas like x, x², and even x + a tiny bit — the ideas you use today when you watch a square grow into x + h and discover 2x. But algebra’s story didn’t stop there.

A century later in Persia, Omar Khayyam — poet, astronomer, and mathematician — tried to solve cubic equations. They were too hard for algebra alone, so he solved them geometrically, using curves and conic sections. He was the first to understand that third-degree equations live in a world of their own.

The Italian Explosion: Cubics, Quartics, and a Big Surprise

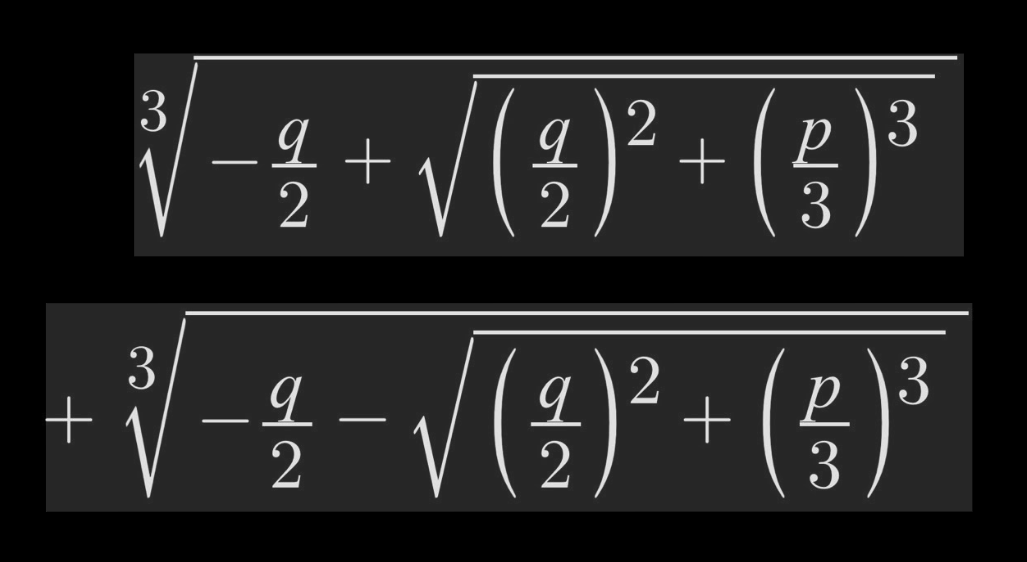

Five hundred years later, in Renaissance Italy, mathematicians raced to solve the cubic algebraically. Tartaglia discovered some of the rules. Cardano published the full solution in his famous book Ars Magna (1545). But something unbelievable happened. While solving certain cubic equations, Cardano’s formulas spit out the square root of –1. This was shocking. Impossible! Meaningless! Yet the answers turned out correct. Enter Rafael Bombelli, who bravely said: “Let’s accept these strange numbers and learn the rules.” He invented the first clear method for computing with what we now call imaginary numbers.

Imaginary numbers were not invented on purpose — they were discovered accidentally while solving cubic equations.

🇪🇺rope The Leap to Calculus

Across Europe, algebra grew stronger: Fermat used algebra to approximate slopes. Torricelli sliced curves into infinitely thin pieces. The Bernoulli brothers used the Power Rule to study motion, tension, and growth.

Finally came Newton and Leibniz, who gave calculus its modern form. Leibniz wrote the very formula your students use today: