🔊 Listen to the story

Click Read to hear the story aloud. You can pause or stop at any time.

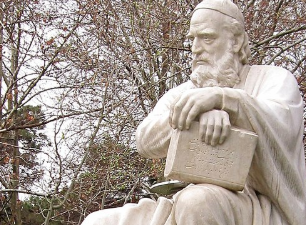

Omar Khayyam - Jalali Calendar - quatrains (Robayat)

Omar Khayyam - Jalali Calendar - quatrains (Robayat)

Galileo and the Secret of Motion

In the early 1600s, when most people believed the universe was already understood, one stubborn Italian scientist refused to accept answers based on tradition alone. His name was Galileo Galilei. Galileo wanted evidence. One question especially bothered him: What really happens when something speeds up? People could measure how fast an object moved at a moment, or how far it traveled overall—but no one understood how distance builds up when speed keeps changing. That missing idea lies at the heart of calculus.

Slowing the World Down: Falling objects moved too fast to study directly, so Galileo did something clever. He slowed motion down. He built a long wooden ramp—an inclined plane—with a smooth groove carved into it. A bronze ball rolled down the ramp slowly enough to observe carefully. To measure time, Galileo used a water clock, letting water drip steadily into a container. At equal time intervals, he marked how far the ball had traveled. What he found was revolutionary: Speed increased steadily; Distance did not increase evenly; Total distance came from adding many small pieces of motion. Galileo did not use integrals—they did not exist yet. But conceptually, he was already doing the same thing students do when they add rectangles under a velocity curve. Motion as Accumulation _ Galileo realized something profound: Distance is not determined by speed at one moment, but by how speed accumulates over time. In modern language, we say: Distance is the area under the velocity curve.

When students estimate distance using larger and then smaller time intervals, and watch their answers converge, they are repeating Galileo’s method—only with graphs instead of ramps.

Looking to the Sky - Galileo’s curiosity extended beyond motion on Earth. When he turned a telescope toward the sky, he observed moons orbiting Jupiter, mountains on the Moon, and the phases of Venus.

A thousand years ago, Persian scholars were among the world’s best observers of the sky. Astronomers like Omar Khayyam measured the Sun’s motion so precisely that the Jalali Calendar he helped design remains one of the most accurate calendars ever created. Their observations helped transform the sky from myth into mathematics.

Fast forward to the 20th century: rockets finally carried us closer to the stars. Before humans flew, scientists sent animals — monkeys, dogs, and chimpanzees — to learn how living bodies react in space. Then, in 1961, Yuri Gagarin became the first human to orbit Earth, calling out, “I see Earth… it is beautiful.” After that the space race started and eight years later, humans walked on the Moon for the very first time.

These discoveries matched the precise planetary data collected earlier by Tycho Brahe, a Danish astronomer who spent decades making the most accurate measurements ever recorded. After Tycho’s death, his assistant Johannes Kepler used that data to discover the true laws of planetary motion—showing that planets move in ellipses and change speed as they orbit. Kepler provided the mathematical laws. Galileo provided the physical understanding. Together, they showed that nature follows patterns that can be measured, accumulated, and understood.

Conflict with Authority - Galileo’s ideas challenged more than science. They challenged authority. Church officials feared that saying Earth moved around the Sun would disrupt long-held beliefs and social order. In 1633, Galileo was forced to recant publicly and spent the rest of his life under house arrest. But evidence could not be un-done.

Why Galileo Matters Here - Galileo taught the world a lasting lesson: Big changes come from adding many small ones. That idea connects distance, velocity, and acceleration—and leads directly to calculus. When you add areas under a curve in this activity, you are not just doing mathematics. You are finishing a discovery Galileo began—one small piece at a time.