🔊 Listen to the story

Click Read to hear the story aloud. You can pause or stop at any time.

ATP: The Curve Behind Every Movement

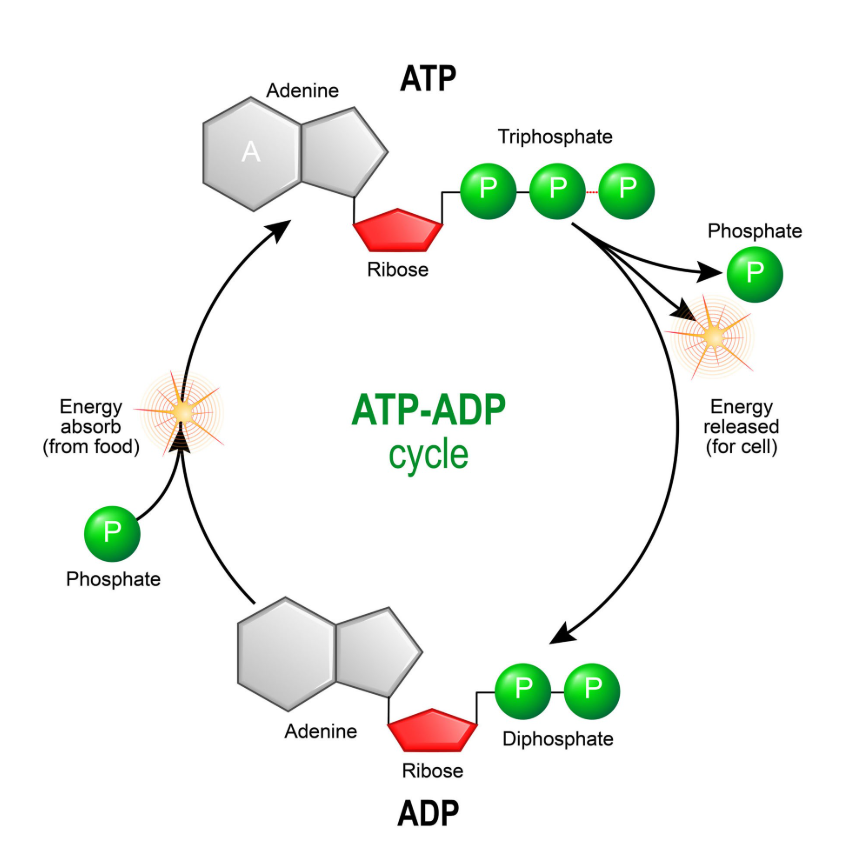

Every movement you have ever made — walking, jumping, throwing a ball, even breathing — has been powered by the same invisible molecule. Not food. Not calories. Not energy in the abstract. A specific molecule called ATP, adenosine triphosphate. ATP is the immediate currency of motion inside your body. When a muscle contracts, ATP is spent. When ATP runs low, motion slows or stops. Long before calculus entered textbooks, ATP was already tracing curves inside living cells.

ATP was identified in the late 1920s, when scientists were trying to answer a deceptively simple question: what actually powers muscle contraction? Working independently, Karl Lohmann, and soon after Cyrus Fiske and Yellapragada Subbarow, isolated a molecule that appeared whenever work was done inside muscle tissue. What made ATP remarkable was not that it stored energy, but that it flowed. It was used, regenerated, and used again, constantly. ATP was not a static reserve. It was a dynamic process unfolding in time.

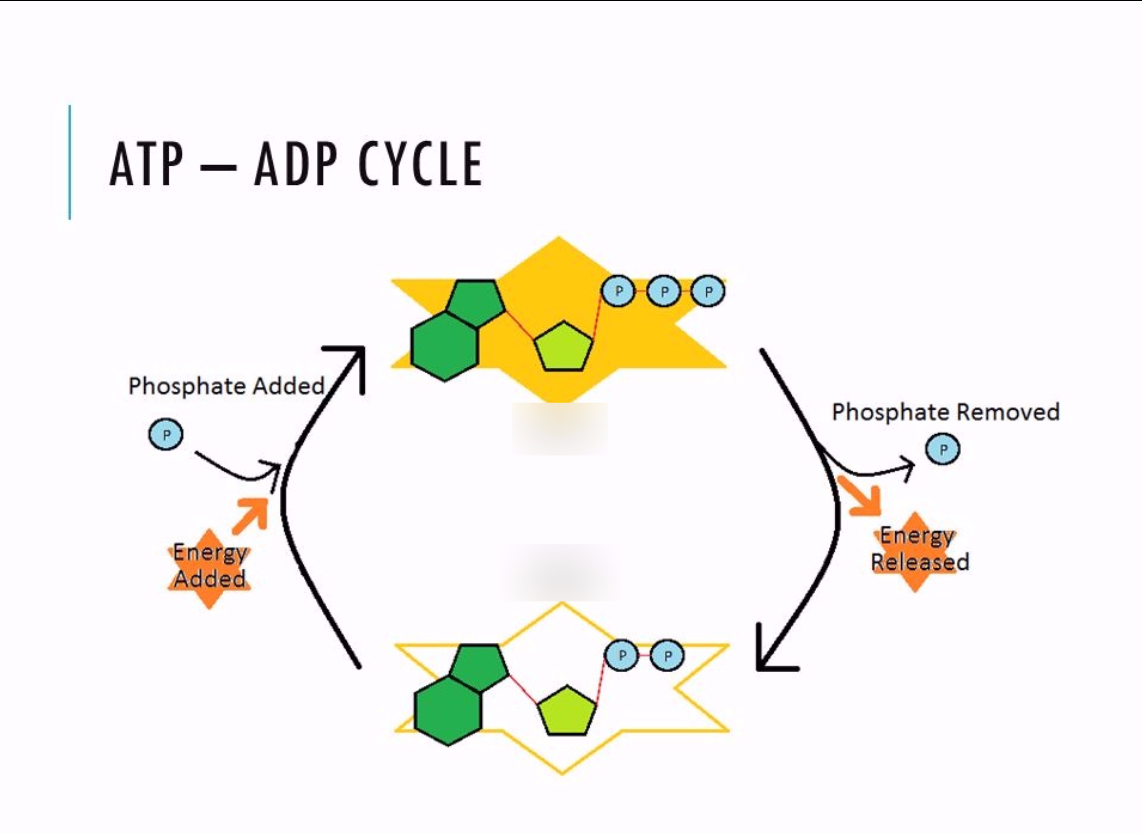

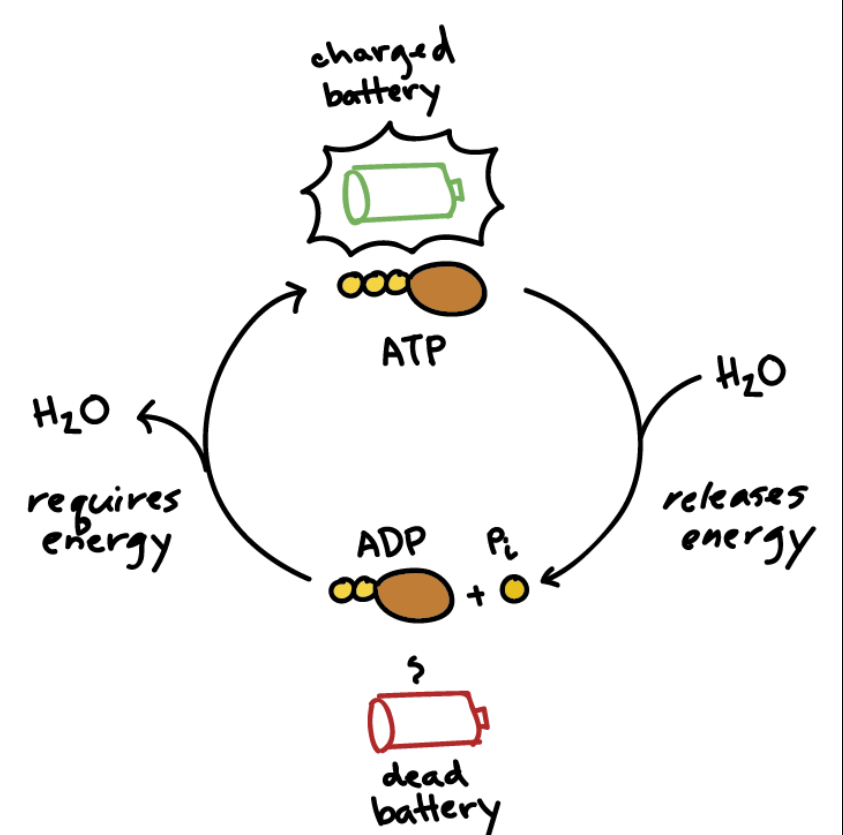

That single fact changes everything. Your body does not stockpile ATP the way a car stores gasoline. At any moment, ATP is being consumed and replenished at the same time. The amount available rises and falls as conditions change. When exercise begins, ATP availability drops. As metabolism responds, production increases. Sometimes ATP stabilizes or even recovers. Eventually, fatigue sets in and availability declines again. This story is not random. It has structure. It has turning points. It has shape.

Once something changes in time, it becomes a function. And once something is a function, it has a graph. ATP availability can be drawn as a curve — not because we like graphs, but because curves are the natural language of change. That curve has a minimum when ATP is most stressed, a maximum when recovery peaks, and a change in concavity when the body shifts strategies. Those features are not guesses. They are enforced by mathematics.

This is where calculus quietly enters biology. Calculus was invented to understand motion, but motion is not only about position and velocity. It is about rates. How fast something changes, and how that rate itself changes. In mechanics we track position, velocity, and acceleration. In biology we can track ATP availability, its rate of change, and how that rate is changing. Different systems — Same logic and same mathematics.

Critical points on a curve — maxima, minima, and inflection points — are not found by looking. They are found by reasoning. A maximum occurs when the first derivative changes from positive to negative. A minimum occurs when it changes from negative to positive. The second derivative tells us why the turn happens — whether the curve bends like a hill or a bowl. Zero slope alone is not enough. Direction change is the key. This rule applies to falling objects, racing cars, and molecules inside muscle cells alike.

There is an old story from ancient Iran about the Parthians, famous horse archers who would appear to retreat from battle, only to turn back in the saddle and release one final, devastating arrow. Historians called it the Parthian shot. Calculus has its own version. After all the algebra and tables, one idea remains standing: you do not need the exact curve to understand the motion. If you know how derivatives behave, you can reconstruct the story.

That final sketch — built from signs, slopes, and concavity — is the real lesson. ATP did not just teach us how muscles move. It shows us why calculus exists at all: to read change, predict turning points, and understand the hidden structure behind motion. That insight is the parting shot — and it carries far beyond this page.